Django Fundamentals

Django is a high-level, free and open-source web framework written in Python. It is widely used for building complex web applications and is known for its ability to handle high traffic, its security features and reusable components. It follows the model-view-controller (MVC) architecture and comes with a built-in admin interface, authentication support and an ORM (Object-Relational Mapper) that allows you to define your database schema using Python classes.

In addition, Django is backed by a large and active community that provides a wealth of tutorials, packages, and other resources for developers to use. Many well-known websites, such as Instagram and Pinterest, are built using Django. It is considered one of the most popular and powerful web frameworks, and in this tutorial, we are going to cover the fundamentals of the Django framework and by the end, you will be able to create Django applications with ease.

You can access the source code for this tutorial here 👈.

Setting up your computer for Django development

To get started, there are a few tools that you need to install on your machine. For a web application, you need at least a programming language (Python), a database (SQLite), and a server (Django's built-in dev server) for the application to run successfully.

However, you should know that this stack is only for the dev environment, SQLite and Django's dev server are not designed for the production environment. You can check out this article on how to deploy Django for production.

And of course, you also need an IDE, such as PyCharm, or at least a code editor. We'll use VS Code for this tutorial since it is a free software.

Creating a new Django project

After everything has been properly installed, it is time to initialize a new project. First of all, you need to create a new work directory to keep everything organized:

mkdir <work_directory>

cd <work_directory>

Replace <work_directory> with your desired name.

Next, create a new Python virtual environment inside the working directory. This virtual environment will be isolated from your system's Python environment, as well as other Python projects you might have on your machine.

python -m venv env

Please note that if you are using Linux or macOS, you might have to run python3 instead of python, but we are going to keep using python in this tutorial for simplicity.

This command will create an env directory containing the virtual environment you just created. You can activate the virtual environment using the following command:

source env/bin/activate

If you are using Windows, use this command instead:

env/Scripts/activate

If the virtual environment has been successfully activated, your terminal prompt will look like this:

(env) eric@djangoDemo:~/django-demo$

(env) means you are currently working inside a virtual environment named env.

Now it is time for us to initialize a new Django project. You need to install the Django package by running the following command:

python -m pip install Django

Next, use the django-admin command to create a new Django project:

django-admin startproject djangoBlog

A new djangoBlog directory will be created:

Optionally, you can restructure the project a bit so that everything starts with the project root directory.

Create a new blog app

Right now, the project is still empty, and as you can see, several files are generated. We'll discuss each file in detail later.

Django allows you to create multiple apps under a single project. For example, there could be a blog app, a gallery app, and a forum app inside one single project. These apps could share the same static files, images, videos, and other resources, or they could be completely independent of each other. It depends entirely on your own choice.

In this tutorial, we’ll create only one blog app for demonstration purposes. Go back to the terminal and execute the following command:

python manage.py startapp blog

You should see a new blog folder generated under the project root directory. Here is a small command-line trick, you can list the content of a directory using the following command:

ls

If you want to include hidden files as well:

ls -a

If you want to see the file structure:

tree

You might have to install tree for the last command to work, depending on your operating system.

From now on, we'll use this command to display the file structure. Right now, your project should have the following structure:

.

├── blog

│ ├── admin.py

│ ├── apps.py

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── migrations

│ ├── models.py

│ ├── tests.py

│ └── views.py

├── djangoBlog

│ ├── asgi.py

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── __pycache__

│ ├── settings.py

│ ├── urls.py

│ └── wsgi.py

├── env

└── manage.py

Next, you need to register this new blog app with Django. Go to settings.py and find INSTALLED_APPS:

INSTALLED_APPS = [

'blog',

'django.contrib.admin',

'django.contrib.auth',

'django.contrib.contenttypes',

'django.contrib.sessions',

'django.contrib.messages',

'django.contrib.staticfiles',

]

Now, you can start the development server to test if everything works. Open the terminal, and run the following command:

python manage.py runserver

You should see the following output:

Watching for file changes with StatReloader

Performing system checks...

System check identified no issues (0 silenced).

You have 18 unapplied migration(s). Your project may not work properly until you apply the migrations for app(s): admin, auth, contenttypes, sessions.

Run 'python manage.py migrate' to apply them.

October 19, 2022 - 01:39:33

Django version 4.1.2, using settings 'djangoBlog.settings'

Starting development server at http://127.0.0.1:8000/

Quit the server with CONTROL-C.

Open the browser and go to http://127.0.0.1:8000/

Django's project structure

Now, let's talk about the structure of this new Django application and what each file does.

.

├── blog

│ ├── admin.py

│ ├── apps.py

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── migrations

│ ├── models.py

│ ├── tests.py

│ └── views.py

├── djangoBlog

│ ├── asgi.py

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── __pycache__

│ ├── settings.py

│ ├── urls.py

│ └── wsgi.py

├── env

└── manage.py

Under the root directory, we have:

manage.py: A command-line utility that lets you interact with this Django project in various ways.djangoBlog: The main project directory, which contains the settings file and the entry point of the project.blog: Theblogapp.

And look inside the project directory, djangoBlog, we have:

djangoBlog/__init__.py: An empty file that tells Python that this directory should be considered a Python package.djangoBlog/settings.py: As the name suggests, it is the setting/configuration file for this Django project.djangoBlog/urls.py: The URL declarations for this Django project, a table of contents of your Django application. We'll talk more about this later.djangoBlog/asgi.py: An entry-point for ASGI-compatible web servers to serve your project.djangoBlog/wsgi.py: An entry-point for WSGI-compatible web servers to serve your project.

And finally, under the application directory, blog, we have:

blog/migrations: This directory contains all the migration files for the blog app. Unlike Laravel, these files are automatically generated by Django based on your models.blog/admin.py: Django also comes with an admin panel, and this file contains all the configurations for it.blog/models.py: Models describe the structure and relation of the database. The migration files are generated based on this file.blog/views.py: This is equivalent to the controllers in Laravel. It contains all the core logic of this app.

Configuring our Django project

Before we delve into our project, there are some changes you need to make to the settings.py file.

- Allowed hosts

The ALLOWED_HOSTS is a list of domains that the Django site is allowed to serve. This is a security measure to prevent HTTP host header attacks, which are possible even under many seemingly-safe web server configurations.

However, you might notice that even if the ALLOWED_HOSTS is currently empty, we can still access our site using the host 127.0.0.1. That is because when DEBUG is True, and ALLOWED_HOSTS is empty, the host is validated against ['.localhost', '127.0.0.1', '[::1]'].

- Database

DATABASES is a dictionary containing the database settings that our website needs to use. By default, Django uses SQLite, which is a very lightweight database consisting of only one file. It should be enough for our small demo project, but it won't work for large sites. So, if you want to use other databases, here is an example:

DATABASES = {

"default": {

"ENGINE": "django.db.backends.postgresql",

"NAME": "<database_name>",

"USER": "<database_user_name>",

"PASSWORD": "<database_user_password>",

"HOST": "127.0.0.1",

"PORT": "5432",

}

}

As a side note, Django recommends using PostgreSQL as your database in a production environment. We are aware that many tutorials are teaching you how to use Django with MongoDB, but that's actually a bad idea. MongoDB is a great database solution, it just doesn't work so well with Django. You can read this article for details.

- Static and media files

And finally, we need to take care of the static and media files. Static files are CSS and JavaScript files, and media files are images, videos, and other things the user might upload.

First, we need to specify where these files are stored. We'll create a static directory inside the blog app for our Django site. This is where we store static files for the blog app during development.

blog

├── admin.py

├── apps.py

├── __init__.py

├── migrations

├── models.py

├── static

├── tests.py

└── views.py

In the production environment, however, things are a bit different. You need a different folder under the root directory of our project. Let's call it staticfiles.

.

├── blog

├── db.sqlite3

├── djangoBlog

├── env

├── manage.py

└── staticfiles

When you put our Django project to production, the files under blog/static will be automatically copied to staticfiles.

Also remember that you need to specify this staticfiles folder in settings.py.

STATIC_ROOT = "staticfiles/"

Next, you need to tell Django what URL to use when accessing these static files. It does not have to be /static, but do make sure it does not overlap with our URL configurations which we'll talk about later.

STATIC_URL = "static/"

Media files are configured in a similar way. You can create a mediafiles folder in the project root directory:

.

├── blog

├── db.sqlite3

├── djangoBlog

├── env

├── manage.py

├── mediafiles

└── staticfiles

And then, specify the location and URL in the settings.py file:

# Media files

MEDIA_ROOT = "mediafiles/"

MEDIA_URL = "media/"

URL dispatchers in Django

In the web development field, there is something we call the MVC (Model-View-Controller) architecture. Under this architecture, the model is in charge of interacting with our database, each model should correspond to one database table. The view is the frontend part of the application, it is what the users can see. And finally, the controller is the central command of the app, it is in charge of tasks such as retrieving data from the database through the models, putting them in the corresponding view, and eventually returning the rendered template back to the user.

Django is designed based on this architecture, just with a different terminology. For Django, it is the MTV (Model-Template-View) structure. The template is the frontend, and the view is the backend logic.

In this tutorial, our focus will be understanding each of these layers, but first, we need to start with the entry point of every web application, the URL dispatcher. What it does is, when the user types in a URL and hits Enter, the dispatcher reads that URL and directs the user to the correct page.

Basic URL configurations

The URL configurations are stored in example/urls.py:

djangoBlog

├── asgi.py

├── __init__.py

├── __pycache__

├── settings.py

├── urls.py <===

└── wsgi.py

The file gives you an example of what an URL dispatcher should look like:

from django.contrib import admin

from django.urls import path

urlpatterns = [

path('admin/', admin.site.urls),

]

It reads information from a URL and returns a view function.

In this example, if the domain is followed by admin/, the dispatcher will route the user to the admin page.

Passing parameters with Django URL dispatchers

In practice, it is often necessary to take a segment from the URL and pass them to the view as parameters. For example, if you want to display a blog post page, you'll need to pass the post id or the slug to the view so that you can use this extra information to find the blog post you are searching for. This is how we can pass a parameter:

from django.urls import path

from blog import views

urlpatterns = [

path('post/<int:id>', views.post),

]

The angle bracket (<int:id>) will capture the segment after post/ as a parameter. Look inside the bracket, on the left side, the int is called a path converter, and it only captures integer parameters. On the right side, it is the name of the parameter. We'll need to use it in the view.

The following path converters are available by default:

str: Matches any non-empty string, excluding the path separator,'/'. This is the default if a converter isn’t included in the expression.int: Matches zero or any positive integer. Returns anint.slug: Matches any slug string consisting of ASCII letters or numbers, plus the hyphen and underscore characters. For example,building-your-1st-django-site.uuid: Matches a formatted UUID. To prevent multiple URLs from mapping to the same page, dashes must be included, and letters must be lowercase. For example,075194d3-6885-417e-a8a8-6c931e272f00. Returns aUUIDinstance.path: Matches any non-empty string, including the path separator,'/'. This allows you to match against a complete URL path rather than a segment of a URL path as withstr.

Using regular expressions to match URL patterns

Sometimes the pattern you need to match is more complicated, in which case you can use regular expressions to describe URL patterns. We discussed regular expressions in detail in the linked lesson.

To enable regular expressions, you need to use re_path() instead of path():

from django.urls import path, re_path

from . import views

urlpatterns = [

path('articles/2003/', views.special_case_2003),

re_path(r'^articles/(?P<year>[0-9]{4})/$', views.year_archive),

re_path(r'^articles/(?P<year>[0-9]{4})/(?P<month>[0-9]{2})/$', views.month_archive),

re_path(r'^articles/(?P<year>[0-9]{4})/(?P<month>[0-9]{2})/(?P<slug>[\w-]+)/$', views.article_detail),

]

Importing other URL configurations

Imagine you have a Django project with multiple different apps in it. If you put all configurations in one file, it will become very messy. When this happens, you can separate the URL configurations and move them to different apps. For example, in our project, we can create a new urls.py inside the blog app.

from django.urls import path, include

urlpatterns = [

path('blog/', include('blog.urls'))

]

This means if the URL has the pattern http://www.example.com/blog/xxxx, Django will go to blog/urls.py and match for the rest of the URL.

Define the URL patterns for the blog app in the exact same way:

from django.urls import path

from blog import views

urlpatterns = [

path('post/<int:id>', views.post),

]

This pattern will match the URL pattern: http://www.mydomain.com/blog/post/123

Naming URL patterns

One last thing we have to discuss is that you can name URL patterns by giving it a third parameter like this:

urlpatterns = [

path('articles/<int:year>/', views.year_archive, name='news-year-archive'),

]

This little trick is very important, it allows us to reverse resolute URLs from the template. We'll talk about this when we get to the template layer.

That is all we need to cover for the basics of URL dispatcher. However, you may have noticed that something is missing. What if we are using differnet HTTP methods? How can we differentiate them?

In Django, you cannot match different HTTP methods inside the URL dispatcher. All methods match the same URL pattern, and we can only differentiate then inside the view functions. We'll discuss this in detail later.

Let's talk about the models

Django's model layer is one of its best features. For other web frameworks, you need to create both a model and a migration file. The migration file is a schema for the database, which describes the structure (column names and column types) of the database. The model provides an interface that handles the data manipulation based on that schema.

But for Django, you only need a model, and the corresponding migration files can be generated with a simple command, saving you a lot of time.

Each app has one models.py file, and all the models related to the app should be defined inside. Each model corresponds to a migration file, which corresponds to a database table. To differentiate tables for different apps, a prefix will be automatically assigned to each table. For our blog app, the corresponding database table will have the prefix blog_.

Here is an example of a model:

blog/models.py

from django.db import models

class Person(models.Model):

first_name = models.CharField(max_length=30)

last_name = models.CharField(max_length=30)

You can then generate a migration file using the following command:

python manage.py makemigrations

And the generated migration file should look like this:

blog/migrations/0001_initial.py

# Generated by Django 4.1.2 on 2022-10-19 23:13

from django.db import migrations, models

class Migration(migrations.Migration):

initial = True

dependencies = []

operations = [

migrations.CreateModel(

name="Person",

fields=[

(

"id",

models.BigAutoField(

auto_created=True,

primary_key=True,

serialize=False,

verbose_name="ID",

),

),

("first_name", models.CharField(max_length=30)),

("last_name", models.CharField(max_length=30)),

],

),

]

The migration file is a schema that describes how the database table should look, you can use the following command to apply this schema:

python manage.py migrate

Your database (db.sqlite3) should look like this:

As a beginner, you should never try to edit or delete the migration files, just let Django do everything for you unless you absolutely know what you are doing. In most cases, Django can detect the changes you've made in the models and generate the migration files accordingly.

In our example, this model will create a blog_phone table, and inside the table, there will be three columns, each named id, first_name, and last_name. The id column is created automatically, as seen in the migration file. The id column is used as the primary key for indexing by default.

CharField() is called a field type and it defines the type of the corresponding column. max_length is a field option, and it specifies extra information about that column. You can find a reference of all field types and field options here.

Model field types and options

To save us some time, we'll only introduce some of the most commonly used field types.

| Field Type | Description |

|---|---|

BigAutoField | Creates an integer column that automatically increments. Usually used for the id column. |

BooleanField | Creates a Boolean value column, with values True or False. |

DateField and DateTimeField | As their names suggest, adds dates and times. |

FileField and ImageField | Creates a column that stores the path, which points to the uploaded file or image. |

IntegerField and BigIntegerField | Integer has values from -2147483648 to 2147483647. Big integer has values from -9223372036854775808 to 9223372036854775807 |

SlugField | Slug is usually a URL-friendly version of the title/name. |

CharField and TextField | CharField and TextField both create a column for storing strings, except TextField corresponds to a larger text box in the Django admin, which we'll talk about later. |

And field options.

| Field Option | Description |

|---|---|

blank | Allows this field to have an empty entry. |

choices | Gives this field multiple choices, you'll see how this works after we get to Django Admin. |

default | Gives the field a default value. |

unique | Makes sure that every item in the column is unique. Usually used to slug and other fields that are supposed to have unique values. |

Meta options

You can also add a Meta class inside the model class, which contains extra information about this model, such as database table name, ordering options, and human-readable singular and plural names.

class Category(models.Model):

priority = models.IntegerField()

class Meta:

ordering = ["priority"]

verbose_name_plural = "categories"

Model methods

Model methods are functions defined inside the model class. These functions allow us to perform custom actions to the current instance of the model object. For example:

class Person(models.Model):

first_name = models.CharField(max_length=50)

last_name = models.CharField(max_length=50)

birth_date = models.DateField()

def baby_boomer_status(self):

"Returns the person's baby-boomer status."

import datetime

if self.birth_date < datetime.date(1945, 8, 1):

return "Pre-boomer"

elif self.birth_date < datetime.date(1965, 1, 1):

return "Baby boomer"

else:

return "Post-boomer"

When the baby_boomer_status() method is called, Django will examine the person's birth date and return the person's baby-boomer status.

Model inheritance

For most web applications, you'll need more than one model, and some of them will have common fields. In this case, you can create a parent model which contains the common fields, and make other models inherit from the parent.

class CommonInfo(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=100)

age = models.PositiveIntegerField()

class Meta:

abstract = True

class Student(CommonInfo):

home_group = models.CharField(max_length=5)

Notice that CommonInfo is marked as an abstract model, which means this model doesn't really correspond to an individual model, instead, it is used as a parent to other models.

To verify this, generate a new migration file:

blog/migrations/0002_student.py

python manage.py makemigrations

# Generated by Django 4.1.2 on 2022-10-19 23:28

from django.db import migrations, models

class Migration(migrations.Migration):

dependencies = [

("blog", "0001_initial"),

]

operations = [

migrations.CreateModel(

name="Student",

fields=[

(

"id",

models.BigAutoField(

auto_created=True,

primary_key=True,

serialize=False,

verbose_name="ID",

),

),

("name", models.CharField(max_length=100)),

("age", models.PositiveIntegerField()),

("home_group", models.CharField(max_length=5)),

],

options={

"abstract": False,

},

),

]

As you can see, only a Student table is created.

Database relations

So far, we've only talked about how to create individual tables, however, in practice, these tables aren't entirely independent, and there are usually relations between different tables. For instance, you could have a category that has multiple posts, a post that belongs to a specific user, etc. So how can you describe such relations in Django?

There are primarily three types of database relations, one-to-one, many-to-one, and many-to-many.

One-to-one relation

The one-to-one relationship should be the easiest to understand. For example, each person could have one phone, and each phone could belong to one person. We can describe this relation in the models like this:

class Person(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=100)

class Phone(models.Model):

person = models.OneToOneField('Person', on_delete=models.CASCADE)

The OneToOneField works just like a regular field type, except it takes at least two arguments. The first argument is the name of the model with whom this model has a relationship. And the second argument is on_delete, which defines the action Django will take when data is deleted. This has more to do with SQL than Django, so we are not going into this topic in detail, but if you are interested, here are some available values for on_delete.

You can now generate and apply migrations for these models and see what happens. If you run into problems running these commands, simply delete the db.sqlite3 file and the migration files to start over.

python manage.py makemigrations

python manage.py migrate

As you can see, the OneToOneField created a person_id column inside the blog_phone table, and this column will store the id of the person that owns this phone.

Many-to-one relation

Each category has many posts, and each post belongs to one category. This relation is referred to as a many-to-one relation.

class Category(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=100)

class Post(models.Model):

category = models.ForeignKey('Category', on_delete=models.CASCADE)

ForeignKey will create a category_id column in the blog_post table, which stores the id of the category that this post belongs to.

Many-to-many relation

Many-to-many relation is slightly more complicated. For example, every article could have multiple tags, and each tag could have multiple articles.

class Tag(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=100)

class Post(models.Model):

tags = models.ManyToManyField('Tag')

Instead of creating a new column, this code will create a pivot table called post_tags, which contains two columns, post_id, and tag_id. This allows you to locate all the tags associated with a particular post, and vice versa.

To make things clearer, imagine we have a table like this:

| post_id | tag_id |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 2 |

| 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 3 |

For a post with id=1, there are two tags, each with id=1 and id=2. If you want to do things backward and find posts through a tag, you can see that for a tag with id=2, there are two posts, id=3 and id=1.

Moving to the view layer

The view layer is one of the most important components in a Django application, it is where we write all the backend logic. The most important thing that views are supposed to do is retrieving data from the database through the corresponding model, processing the retrieved data, putting them in the corresponding location in the template, and finally, rendering and returning that template back to the user.

Of course, that is not the only thing we can do with a view function. In most web applications, there are four most basic operations we can do with data, create, read, update and delete them. These operations put together are often referred to as CRUD. We are going to investigate all of them in this tutorial later.

We've briefly discussed models in the previous section, but we still don't know how to retrieve or store data using the model. Django offers us a very simple API to help us with that, which is called the QuerySet.

Suppose that this is your model:

blog/models.py

class Category(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=100)

class Tag(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=200)

class Post(models.Model):

title = models.CharField(max_length=255)

content = models.TextField()

pub_date = models.DateField()

category = models.ForeignKey(Category, on_delete=models.CASCADE)

tags = models.ManyToManyField(Tag)

With the help of QuerySet, you can manipulate data through this model inside the view functions, which are located inside the blog/views.py file.

Creating and saving data

Let's say you are trying to create a new category, this is what you can do:

# import the Category model

from blog.models import Category

# create a new instance of Category

category = Category(name="New Category")

# save the newly created category to database

category.save()

In this example, we created a new instance of the Category object and used the save() method to save the information to the database.

Now, what about relations? For example, there is a many-to-one relationship between category and post, which we defined using the ForeignKey() field.

from blog.models import Category, Post

# Post.objects.get(pk=1) is how we retrieve the post with pk=1,

# where pk stands for primary key, which is usually the id unless otherwise specified.

post = Post.objects.get(pk=1)

# retrieve the category with name="New Category"

new_category = Category.objects.get(name="New Category")

# assign new_category to the post's category field and save it

post.category = new_category

post.save()

There is also a many-to-many relation between posts and tags.

from blog.models import Tag, Post

post1 = Post.objects.get(pk=1) # Retrieve post 1

tag1 = Tag.objects.get(pk=1) # Retrieve tag 1

tag2 = Tag.objects.get(pk=2) # Retrieve tag 2

tag3 = Tag.objects.get(pk=3) # Retrieve tag 3

tag4 = Tag.objects.get(pk=4) # Retrieve tag 4

tag5 = Tag.objects.get(pk=5) # Retrieve tag 5

post.tags.add(tag1, tag2, tag3, tag4, tag5) # Add tag 1-5 to post 1

Retrieving data

Retrieving objects is slightly more complicated. Imagine we have thousands of records in our database. How do we find one particular record, if we don't know the id? Or, what if we want a collection of records that fits particular criteria instead of one record?

The QuerySet methods allow you to retrieve data based on certain criteria. And they can be accessed using the attribute objects. We've already seen an example, get(), which is used to retrieve one particular record.

first_tag = Tag.objects.get(pk=1)

new_category = Category.objects.get(name="New Category")

You can also retrieve all records using the all() method.

Post.objects.all()

The all() method returns what we call a QuerySet, it is a collection of records. And you can further refine that collection by chaining a filter() or exclude() method.

Post.objects.all().filter(pub_date__year=2006)

This will return all the posts that are published in the year 2006. And pub_date__year is called a field lookup.

Or we can exclude the posts that are published in the year 2006.

Post.objects.all().exclude(pub_date__year=2006)

Besides get(), all(), filter() and exclude(), there are lots of other QuerySet methods just like them. We can't talk about all of them here, but if you are interested, here is a full list of all QuerySet methods.

Field lookups are the keyword arguments for QuerySet methods. If you are familiar with SQL, they work just like the SQL WHERE clause. And they take the form fieldname__lookuptype=value. Notice that it is a double underscore in between.

Post.objects.all().filter(pub_date__lte='2006-01-01')

In this example, pub_date is the field name, and lte is the lookup type, which means less than or equal to. This code will return all the posts where the pub_date is less than or equal to 2006-01-01.

Here is a list of all field lookups you can use.

Field lookups can also be used to find records that have a relationship with the current record. For example:

Post.objects.filter(category__name='Django')

This line of code will return all posts that belong to the category whose name is "Django".

This works backward too. For instance, we can return all the categories that have at least one post whose title contains the word "Django".

Category.objects.filter(post__title__contains='Django')

We can go across multiple relations as well.

Category.objects.filter(post__author__name='Admin')

This will return all categories that own posts, which are published by the user Admin. In fact, you can chain as many relationships as you want.

Deleting Objects

The method we use to delete a record is conveniently named delete(). The following code will delete the post that has pk=1.

post = Post.objects.get(pk=1)

post.delete()

We can also delete multiple records together.

Post.objects.filter(pub_date__year=2005).delete()

This will delete all posts that are published in the year 2005.

However, what if the record we are deleting relates to another record? For example, here we are trying to delete a category with multiple posts.

category = Category.objects.get(pk=1)

category.delete()

By default, Django emulates the behaviour of the SQL constraint ON DELETE CASCADE, which means all the posts that belong to this category also be deleted. If you wish to change that, you can change the on_delete option to something else. Here is a reference of all available options for on_delete.

The view function

So far, we've only seen some snippets showing what you can do inside a view function, but what does a complete view function look like? Well, here is an example. In Django, all the views are defined inside the views.py file.

from django.shortcuts import render

from blog.models import Post

# Create your views here.

def my_view(request):

posts = Post.objects.all()

return render(request, 'blog/index.html', {

'posts': posts,

})

There are two things you need to pay attention to in this example.

First, notice that this view function takes an input request. This variable request is an HttpRequest object, and it is automatically passed to the view from our URL dispatcher.

The request contains information about the current HTTP request. For example, we can access the HTTP request method and create different logic for different methods.

if request.method == 'GET':

do_something()

elif request.method == 'POST':

do_something_else()

Here is a list of all the information you can access from request.

Second, notice that a shortcut called render() is used to pass the variable posts to the template blog/index.html.

This is called a shortcut because, by default, you are supposed to load the template with the loader() method, render that template with the retrieved data, and return an HttpResponse object. Django simplified this process with the render() method. To make life easier for you, we are not going to talk about the complex way here, since we will not use it in this tutorial anyway.

Here is a list of all shortcut functions in Django.

Django's template system

Now, let's talk about templates. The template layer is the frontend part of a Django application, which is why the template files are all HTML code since they are what you see in the browser, but things are slightly more complicated than that. If it contains only HTML code, the entire website would be static, and that is not what we want. So the template would have to tell the view function where to put the retrieved data.

Configurations for the template

Before we start, there is something you need to change in the settings.py, you must tell Django where you are putting the template files.

First, create the templates directory. FOr this tutorial, we choose to put it under the root directory of the project, but you can move it somewhere else if you want.

.

├── blog

├── db.sqlite3

├── djangoBlog

├── env

├── manage.py

├── mediafiles

├── staticfiles

└── templates

Go to settings.py and find TEMPLATES.

TEMPLATES = [

{

'BACKEND': 'django.template.backends.django.DjangoTemplates',

'DIRS': [

'templates',

],

'APP_DIRS': True,

'OPTIONS': {

'context_processors': [

'django.template.context_processors.debug',

'django.template.context_processors.request',

'django.contrib.auth.context_processors.auth',

'django.contrib.messages.context_processors.messages',

],

},

},

]

Change the DIRS option, which points to the template folder. Now let's verify that this setting works. Create a new URL pattern that points to a test() view.

djangoBlog/urls.py

from django.urls import path

from blog import views

urlpatterns = [

path('test/', views.test),

]

Create the test() view:

blog/views.py

def test(request):

return render(request, 'test.html')

Go to the templates folder and create a test.html template:

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="IE=edge" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" />

<title>Test Page</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>This is a test page.</p>

</body>

</html>

Start the dev server and go to http://127.0.0.1:8000/.

The Django template language

Now let's discuss Django's template engine in detail. Recall that we can send data from the view to the template like this:

def test(request):

return render(request, 'test.html', {

'name': 'Jack'

})

The string 'Jack' is assigned to the variable name and passed to the template. And inside the template, we can display the name using double curly braces, {{ }}.

<p>Hello, {{ name }}</p>

Refresh the browser, and you will see the output.

However, in most cases, the data that is passed to the template is not a simple string. For example:

def test(request):

post = Post.objects.get(pk=1)

return render(request, 'test.html', {

'post': post

})

In this case, the post variable is, in fact, a dictionary. You can access the items in that dictionary like this:

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.content }}

{{ post.pub_date }}

Sometimes, instead of displaying the retrieved data directly, you might need to perform certain transformations first, such as turn then upper or lower cases. You can use filters to achieve this effect. For example, we have a variable django, with the value 'the web framework for perfectionists with deadlines'. If we put a title filter on this variable:

{{ django|title }}

The template will be rendered into:

The Web Framework For Perfectionists With Deadlines

Here is a full list of all built-in filters in Django.

Besides simple transformations, you might also want to add programming language features such as flow control and loops to HTML code. This is called tags in Django template engine. All tags are defined using {% %}.

For example, this is a for loop:

<ul>

{% for athlete in athlete_list %}

<li>{{ athlete.name }}</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

This is an if statement:

{% if somevar == "x" %}

This appears if variable somevar equals the string "x"

{% endif %}

And this is an if-else statement:

{% if athlete_list %}

Number of athletes: {{ athlete_list|length }}

{% elif athlete_in_locker_room_list %}

Athletes should be out of the locker room soon!

{% else %}

No athletes.

{% endif %}

Here is a full list of all built-in tags in Django. There are lots of other useful filters and tags in Django template system, we'll talk about them as we encounter specific problems.

The inheritance system

The primary benefit of using the Django template is that you do not need to write the same code over and over again. For example, in a typical web application, there is usually a navigation bar and a footer, which will appear on every page. Repeating all of these code on every page will make it very difficult for maintenance. Django offers us a easy way to solve this problem.

Let’s create a layout.html file in the templates folder. As the name suggests, this is the place where we define the layout of our template. To make this example easier to read, we skipped the code for the footer and navbar.

layout.html

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

{% block meta %} {% endblock %}

<!-- Import CSS here -->

</head>

<body>

<div class="container">

<!-- Put the navbar here -->

{% block content %} {% endblock %}

<!-- Put the footer here -->

</div>

</body>

</html>

Notice that in this file, we defined two blocks, meta and content, using the {% block ... %} tag. next, we define a home.html template that uses this layout.

home.html

{% extends 'layout.html' %}

{% block meta %}

<title>Page Title</title>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<meta name="description" content="Free Web tutorials">

<meta name="keywords" content="HTML, CSS, JavaScript">

<meta name="author" content="John Doe">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<p>This is the content section.</p>

{% include 'vendor/sidebar.html' %}

{% endblock %}

When this template is called, Django will first find the layout.html file, and fill the meta and content blocks with snippets defined in this home.html page.

Also notice there is something else in this template. {% include 'vendor/sidebar.html' %} tells Django to look for the templates/vendor/sidebar.html and place it here.

sidebar.html

<p>This is the sidebar.</p>

It is not exactly a sidebar, but we can use it to demonstrate this inheritance system works. Also make sure your corresponding view is correct.

from django.shortcuts import render

def home(request):

return render(request, 'home.html')

And make sure your URL dispatcher points to this view.

path('home/', views.home),

Open your browser and go to http://127.0.0.1:8000/home, and you should see the following page:

Create your first app

We introduced many new concepts in the previous sections, and you probably feel a bit overwelmed. But don't worry, in this section, we will dig deeper and find out how the URL dispatchers, models, views, and templates can work together to create a functional Django application.

To make things easier to understand, we are not going to create a full-featured blog application with categories, tags and etc. Instead, we will create only a post page that displays a post article, a home page that shows a list of all articles, and a create/update/delete page that modifies the post.

Designing the database structure

Let's start with the model layer. The first thing you need to do is design the database structure. Since we are only dealing with posts right now, you can go ahead to the models.py file, and create a new Post model:

blog/models.py

from django.db import models

class Post(models.Model):

title = models.CharField(max_length=100)

content = models.TextField()

This Post contains only two fields, title, which is a CharField with a maximum of 100 characters, and content, which is a TextField.

Generate the corresponding migration files with the following command:

python manage.py makemigrations

Apply the migrations:

python manage.py migrate

The CRUD operations

Now, it is time for us to delve into the application itself. When building real-life applications, it is unlikely that you can create all the controllers first, and then design the templates, and then move on to the routers. Instead, you need to think from the user's perspective, and think about what actions the user might want to take.

In general, the user should have the ability to perform four operations on each resource, which in our case, is the Post.

- Create: This operation is used to insert new data into the database.

- Read: This operation is used to retrieve data from the database.

- Update: This operation is used to modify existing data in the database.

- Delete: This operation is used to remove data from the database.

Together, they are referred to as the CRUD operations.

- The create action

First, let's start with the create action. Currently, the database is still empty, so the user must create a new post. To complete this create action, you need a URL dispatcher that points the URL pattern /post/create/ to the post_create() view function.

A flow control should be implemented inside the post_create() function, if the request method is GET, return a template that contains an HTML form, allowing the user to pass information to the backend. When the form is submitted, a POST request should be sent to the same view function, in which case a new Post resource should be created and saved.

Let us start with the URL dispatcher, go to urls.py:

djangoBlog/urls.py

from django.urls import path

from blog import views

urlpatterns = [

path("post/create/", views.post_create, name="create"),

]

Then you'll need a post_create() view function. Go to views.py and add the following code:

blog/views.py

from django.shortcuts import redirect, render

from .models import Post

def post_create(request):

if request.method == "GET":

return render(request, "post/create.html")

elif request.method == "POST":

post = Post(title=request.POST["title"], content=request.POST["content"])

post.save()

return redirect("home")

The post_create() function first examines the method of the HTTP request, if it is a GET method, return the create.html template, if it is a POST, use the information passed by that POST request to create a new Post instance, and after it is done, redirect to the home page (we'll create this page in the next step).

Next, time to create the create.html template. First of all, you need a layout.html:

templates/layout.html

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="IE=edge" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" />

<script src="https://cdn.tailwindcss.com"></script>

{% block title %}{% endblock %}

</head>

<body class="container mx-auto font-serif">

<div class="bg-white text-black font-serif">

<div id="nav">

<nav class="flex flex-row justify-between h-16 items-center shadow-md">

<div class="px-5 text-2xl">

<a href="/">My Blog</a>

</div>

<div class="hidden lg:flex content-between space-x-10 px-10 text-lg">

<a

href="{% url 'create' %}"

class="hover:underline hover:underline-offset-1"

>New Post</a

>

<a

href="https://github.com/thedevspacehq"

class="hover:underline hover:underline-offset-1"

>GitHub</a

>

</div>

</nav>

</div>

{% block content %}{% endblock %}

<footer class="bg-gray-700 text-white">

<div

class="flex justify-center items-center sm:justify-between flex-wrap lg:max-w-screen-2xl mx-auto px-4 sm:px-8 py-10">

<p class="font-serif text-center mb-3 sm:mb-0">

Copyright ©

<a href="https://www.thedevspace.io/" class="hover:underline"

>TheDevSpace</a

>

</p>

<div class="flex justify-center space-x-4">. . .</div>

</div>

</footer>

</div>

</body>

</html>

Notice the {% url 'create' %} on line 20. This is how you can reverse resolute URLs based on their names. The name create matches the name you gave to the post/create/ dispatcher.

We also added TailwindCSS through a CDN on line 7 to make this page look better, but you shouldn't do this in the production environment.

Next, create the create.html template. We choose to create a post directory to make it clear that this template is for creating a post, but you can do this differently as long as it makes sense to you:

templates/post/create.html

{% extends 'layout.html' %}

{% block title %}

<title>Create</title>

{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<div class="w-96 mx-auto my-8">

<h2 class="text-2xl font-semibold underline mb-4">Create new post</h2>

<form action="{% url 'create' %}" method="POST">

{% csrf_token %}

<label for="title">Title:</label><br />

<input

type="text"

id="title"

name="title"

class="p-2 w-full bg-gray-50 rounded border border-gray-300 focus:ring-3 focus:ring-blue-300" />

<br />

<br />

<label for="content">Content:</label><br />

<textarea

type="text"

id="content"

name="content"

rows="15"

class="p-2 w-full bg-gray-50 rounded border border-gray-300 focus:ring-3 focus:ring-blue-300"></textarea>

<br />

<br />

<button

type="submit"

class="font-sans text-white bg-blue-700 hover:bg-blue-800 focus:ring-4 focus:outline-none focus:ring-blue-300 font-medium rounded-md text-sm w-full px-5 py-2.5 text-center">

Submit

</button>

</form>

</div>

{% endblock %}

Line 10 specifies the action this form will take when it is submitted, as well as the request method it will use.

Line 11 adds CSRF protection to the form for security purposes.

Also pay attention to the <input> field on line 14 to 18. Its name attribute is very important. When the form is submitted, the user input will be tied to this name attribute, and you can then retrieve that input in the view function like this:

title=request.POST["title"]

Same for the <textarea> on line 24 to 29.

And finally, the button must have type="submit" for it to work.

- The list action

Now let's create a home page where you can show a list of all posts. You can start with the URL again:

djangoBlog/urls.py

path("", views.post_list, name="home"),

And then the view function:

blog/views.py

def post_list(request):

posts = Post.objects.all()

return render(request, "post/list.html", {"posts": posts})

The list.html template:

{% extends 'layout.html' %}

{% block title %}

<title>My Blog</title>

{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<div class="max-w-screen-lg mx-auto my-8">

{% for post in posts %}

<h2 class="text-2xl font-semibold underline mb-2">

<a href="{% url 'show' post.pk %}">{{ post.title }}</a>

</h2>

<p class="mb-4">{{ post.content | truncatewords:50 }}</p>

{% endfor %}

</div>

{% endblock %}

The {% for post in posts %} iterates over all posts, and each item is assigned to the variable post.

The {% url 'show' post.pk %} passes the primary key of the post to the show URL dispatcher, which we'll create later.

And finally, {{ post.content | truncatewords:50 }} uses a filter truncatewords to truncate the content, so that only the first 50 words are kept.

- The show action

Next, the show action should display the content of a particular post, which means its URL should contain something unique that allows Django to locate just one Post instance. That something is usually the primary key.

djangoBlog/urls.py

path("post/<int:id>", views.post_show, name="show"),

The integer following post/ will be assigned to the variable id, and passed to the view function.

blog/views.py

def post_show(request, id):

post = Post.objects.get(pk=id)

return render(request, "post/show.html", {"post": post})

And again, the corresponding template:

templates/post/show.html

{% extends 'layout.html' %}

{% block title %}

<title>{{ post.title }}</title>

{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<div class="max-w-screen-lg mx-auto my-8">

<h2 class="text-2xl font-semibold underline mb-2">{{ post.title }}</h2>

<p class="mb-4">{{ post.content }}</p>

<a

href="{% url 'update' post.pk %}"

class="font-sans text-white bg-blue-700 hover:bg-blue-800 focus:ring-4 focus:outline-none focus:ring-blue-300 font-medium rounded-md text-sm w-full px-5 py-2.5 text-center"

>Update</a

>

</div>

{% endblock %}

- The update action

The URL dispatcher:

djangoBlog/urls.py

path("post/update/<int:id>", views.post_update, name="update"),

The view function:

blog/views.py

def post_update(request, id):

if request.method == "GET":

post = Post.objects.get(pk=id)

return render(request, "post/update.html", {"post": post})

elif request.method == "POST":

post = Post.objects.update_or_create(

pk=id,

defaults={

"title": request.POST["title"],

"content": request.POST["content"],

},

)

return redirect("home")

The update_or_create() method is a new method added in Django 4.1.

The corresponding template:

templates/post/update.html

{% extends 'layout.html' %}

{% block title %}

<title>Update</title>

{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<div class="w-96 mx-auto my-8">

<h2 class="text-2xl font-semibold underline mb-4">Update post</h2>

<form action="{% url 'update' post.pk %}" method="POST">

{% csrf_token %}

<label for="title">Title:</label><br />

<input

type="text"

id="title"

name="title"

value="{{ post.title }}"

class="p-2 w-full bg-gray-50 rounded border border-gray-300 focus:ring-3 focus:ring-blue-300" />

<br />

<br />

<label for="content">Content:</label><br />

<textarea

type="text"

id="content"

name="content"

rows="15"

class="p-2 w-full bg-gray-50 rounded border border-gray-300 focus:ring-3 focus:ring-blue-300">

{{ post.content }}</textarea

>

<br />

<br />

<div class="grid grid-cols-2 gap-x-2">

<button

type="submit"

class="font-sans text-white bg-blue-700 hover:bg-blue-800 focus:ring-4 focus:outline-none focus:ring-blue-300 font-medium rounded-md text-sm w-full px-5 py-2.5 text-center">

Submit

</button>

<a

href="{% url 'delete' post.pk %}"

class="font-sans text-white bg-red-700 hover:bg-red-800 focus:ring-4 focus:outline-none focus:ring-red-300 font-medium rounded-md text-sm w-full px-5 py-2.5 text-center"

>Delete</a

>

</div>

</form>

</div>

{% endblock %}

- The delete action

Finally, for the delete action:

djangoBlog/urls.py

path("post/delete/<int:id>", views.post_delete, name="delete"),

blog/views.py

def post_delete(request, id):

post = Post.objects.get(pk=id)

post.delete()

return redirect("home")

This action does not require a template, since it just redirects you to the home page after the action is completed.

Finally, let's start the dev server and see the result.

python manage.py runserver

The home page:

The create page:

The show page:

The update page:

One step forward

Finally, it is time for us to take one last step forward, and create a fully featured blog application using Django. We explored how the model, view, and template may work together to create a Django application in the previous section, but frankly, it is a tedious process since you have to write at least 5 actions for each feature, and most of the code feels repetitive.

So in this section, we are going to utilize one of the best features of Django, it's built-in admin panel. For most features you wish to create for your application, you only need to write the show/list action, and Django will automatically take care of the rest for you.

Create the model layer

Again, let's start by designing the database structure.

For a basic blogging system, you need at least 4 models: User, Category, Tag, and Post. In the next article, we will add some advanced features, but for now, these four models are all you need.

- The

Usermodel

| key | type | info |

|---|---|---|

| id | integer | auto increment |

| name | string | |

| string | unique | |

| password | string |

The User model is already included in Django, and you don’t need to do anything about it. The built-in User model provides some basic features, such as password hashing, and user authentication, as well as a built-in permission system integrated with the Django admin. You'll see how this works later.

- The

Categorymodel

| key | type | info |

|---|---|---|

| id | integer | auto increment |

| name | string | |

| slug | string | unique |

| description | text |

- The

Tagmodel

| key | type | info |

|---|---|---|

| id | integer | auto increment |

| name | string | |

| slug | string | unique |

| description | text |

- The

Postmodel

| key | type | info |

|---|---|---|

| id | integer | auto increment |

| title | string | |

| slug | string | unique |

| content | text | |

| featured_image | string | |

| is_published | boolean | |

| is_featured | boolean | |

| created_at | date |

- The

Sitemodel

And of course, you need another table that stores the basic information of this entire website, such as name, description and logo.

| key | type | info |

|---|---|---|

| name | string | |

| description | text | |

| logo | string |

And finally, for this blog application, there are six relations you need to take care of.

- Each user has multiple posts

- Each category has many posts

- Each tag belongs to many posts

- Each post belongs to one user

- Each post belongs to one category

- Each post belongs to many tags

Next, it’s time to implement this design.

First of all, you need a Site model.

class Site(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=200)

description = models.TextField()

logo = models.ImageField(upload_to="logo/")

class Meta:

verbose_name_plural = "site"

def __str__(self):

return self.name

Notice the ImageField(), this field is, in fact, a string type. Since databases can't really store images, instead, the images are stored in your server's file system, and this field will keep the path that points to the image's location.

In this example, the images will be uploaded to mediafiles/logo/ directory. Recall that we defined MEDIA_ROOT = "mediafiles/" in settings.py file.

For this ImageField() to work, you need to install Pillow on your machine:

pip install Pillow

The Category model should be easy to understand.

class Category(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=200)

slug = models.SlugField(unique=True)

description = models.TextField()

class Meta:

verbose_name_plural = "categories"

def __str__(self):

return self.name

However, we do need to talk about the Meta class. This is how you add metadata to your models.

Recall that model's metadata is anything that’s not a field, such as ordering options, database table name, etc. In this case, we use verbose_name_plural to define the plural form of the word category. Unfortunately, Django is not as "smart" in this particular aspect, if you don't give Django the correct plural form, it will use categorys instead.

And the __str__(self) function defines what field Django will use when referring to a particular category, in our case, we are using the name field. It will become clear why this is necessary when you get to the Django admin section.

And next, we have the Tag model.

class Tag(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=200)

slug = models.SlugField(unique=True)

description = models.TextField()

def __str__(self):

return self.name

As well as the Post model.

from ckeditor.fields import RichTextField

. . .

class Post(models.Model):

title = models.CharField(max_length=200)

slug = models.SlugField(unique=True)

content = RichTextField()

featured_image = models.ImageField(upload_to="images/")

is_published = models.BooleanField(default=False)

is_featured = models.BooleanField(default=False)

created_at = models.DateField(auto_now=True)

# Define relations

category = models.ForeignKey(Category, on_delete=models.CASCADE)

tag = models.ManyToManyField(Tag)

user = models.ForeignKey(settings.AUTH_USER_MODEL, on_delete=models.CASCADE)

def __str__(self):

return self.title

Line 1, if you just copy and paste this code, your editor will tell you that it cannot find the RichTextField and ckeditor. That is because it is a third-party package, and it is not included in the Django framework.

Recall that in the previous section, you can only add plain text when creating a new post, and that is not ideal for a blog article. The rich text editor or WYSIWYG HTML editor allows you to edit HTML pages directly without writing the code. In this tutorial, we are using the CKEditor as an example.

To install CKEditor, run the following command:

pip install django-ckeditor

After that, register ckeditor in settings.py:

INSTALLED_APPS = [

"blog",

"ckeditor",

"django.contrib.admin",

"django.contrib.auth",

"django.contrib.contenttypes",

"django.contrib.sessions",

"django.contrib.messages",

"django.contrib.staticfiles",

]

Finally, you must add relations to the models. For this project, we only need to add three lines of code in the Post model:

category = models.ForeignKey(Category, on_delete=models.CASCADE)

tag = models.ManyToManyField(Tag)

user = models.ForeignKey(settings.AUTH_USER_MODEL, on_delete=models.CASCADE)

And since we are using the built-in User model (settings.AUTH_USER_MODEL), remember to import the settings module.

from django.conf import settings

Last but not least, generate the migration files and apply them to the database.

python manage.py makemigrations

python manage.py migrate

Set up the admin panel

Our next step would be setting up the admin panel. Django comes with a built-in admin system, and to use it, all you need to do is just register a superuser by running the following command:

python manage.py createsuperuser

And then, you can access the admin panel by going to http://127.0.0.1:8000/admin/.

Right now, the admin panel is still empty, there is only an authentication tab, which you can use to assign different roles to different users. This is a rather complicated topic requiring another tutorial article, so we will not cover that right now. Instead, we focus on how to connect your blog app to the admin system.

Inside the blog app, you should find a file called admin.py. Add the following code to it.

blog/admin.py

from django.contrib import admin

from .models import Site, Category, Tag, Post

# Register your models here.

class CategoryAdmin(admin.ModelAdmin):

prepopulated_fields = {"slug": ("name",)}

class TagAdmin(admin.ModelAdmin):

prepopulated_fields = {"slug": ("name",)}

class PostAdmin(admin.ModelAdmin):

prepopulated_fields = {"slug": ("title",)}

admin.site.register(Site)

admin.site.register(Category, CategoryAdmin)

admin.site.register(Tag, TagAdmin)

admin.site.register(Post, PostAdmin)

On line 2, import the models you just created, and then register the imported model using admin.site.register(). Notice that when you register the Category model, there is something extra called CategoryAdmin, which is a class that is defined on line 6. This is how you can pass some extra information to the Django admin system.

Here you can use prepopulated_fields to generate slugs for all categories, tags, and posts. The value of the slug will be depended on the name. Let's test it by creating a new category.

Go to http://127.0.0.1:8000/admin/. Click on Categories, and add a new category. Remember we defined the plural form of Category in our model? This is why it is necessary, if we don't do that, Django will use Categorys instead.

Notice that the slug will be automatically generated as you type in the name. Try adding some dummy data, everything should work smoothly.

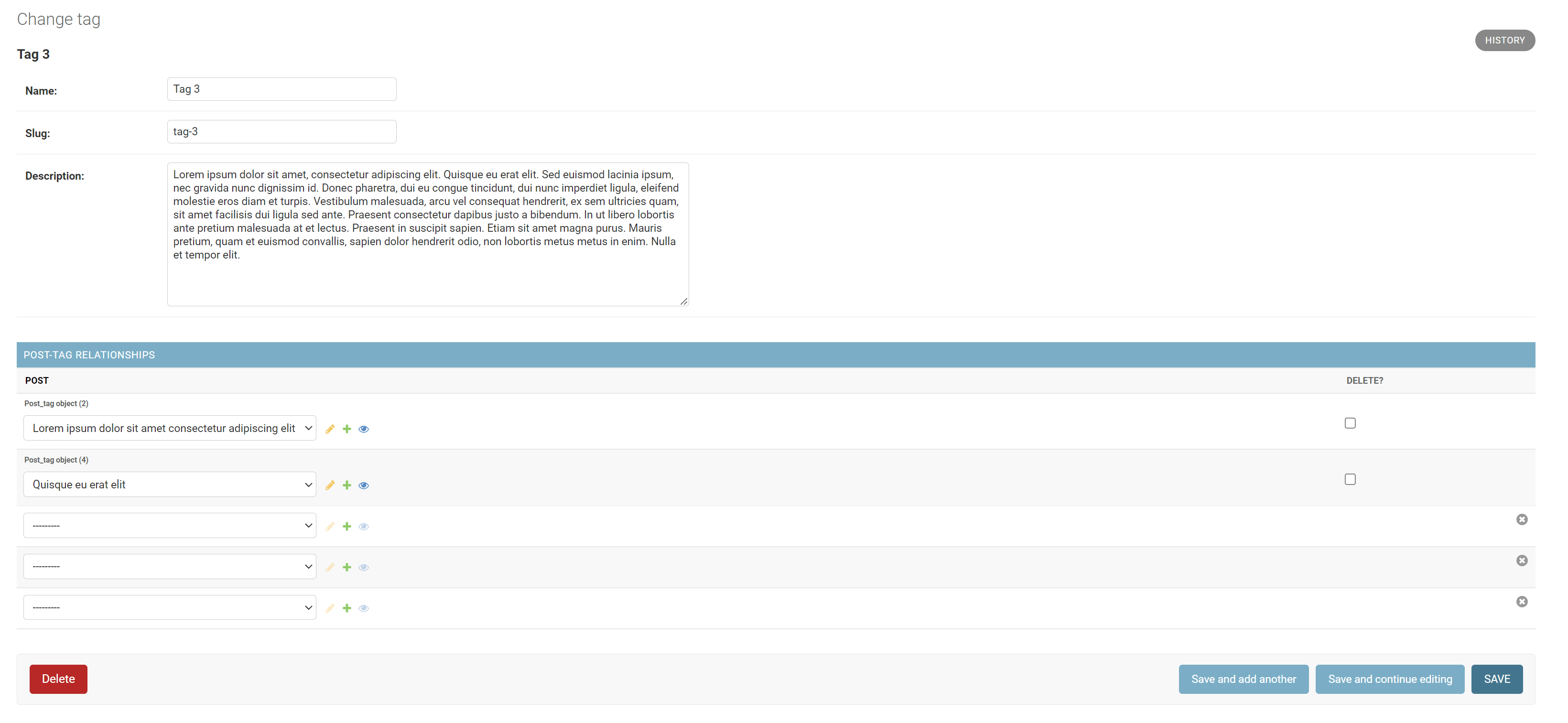

However, our work is not done yet. Open the category panel, you will notice that you can access categories from the post page, but there is no way to access corresponding posts from the category page. If you don't think that's necessary, you can jump to the next section. But if you want to solve this problem, you must add a InlineModelAdmin.

blog/admin.py

class PostInlineCategory(admin.StackedInline):

model = Post

max_num = 2

class CategoryAdmin(admin.ModelAdmin):

prepopulated_fields = {"slug": ("name",)}

inlines = [

PostInlineCategory

]

First, create a PostInlineCategory class, and then use it in the CategoryAdmin. max_num = 2 means only two posts will be shown on the category page. This is how it looks:

Next, you can do the same for the TagAdmin.

blog/admin.py

class PostInlineTag(admin.TabularInline):

model = Post.tag.through

max_num = 5

class TagAdmin(admin.ModelAdmin):

prepopulated_fields = {"slug": ("name",)}

inlines = [

PostInlineTag

]

The code is very similar, but notice the model is not just Post, it is Post.tag.through. That is because the relationship between Post and Tag is a many-to-many relationship. This is the final result.

Build the view layer

Since we have the admin panel set up for our blog application, you don't need to build the full CRUD operations on your own. Instead, you only need to worry about how to retrieve information from the database. You need four pages, home, category, tag, and post, and you'll need one view function for each of them.

- The

homeview

blog/views.py

from .models import Site, Category, Tag, Post

def home(request):

site = Site.objects.first()

posts = Post.objects.all().filter(is_published=True)

categories = Category.objects.all()

tags = Tag.objects.all()

return render(request, 'home.html', {

'site': site,

'posts': posts,

'categories': categories,

'tags': tags,

})

Line 1, import the necessary models.

Line 4, site contains the basic information of our website, and we are always retrieving the first record in the database.

Line 5, filter(is_published=True) ensures that only published articles will be displayed.

Next, don't forget the corresponding URL dispatcher.

djangoBlog/urls.py

path('', views.home, name='home'),

- The

categoryview

blog/views.py

def category(request, slug):

site = Site.objects.first()

posts = Post.objects.filter(category__slug=slug).filter(is_published=True)

requested_category = Category.objects.get(slug=slug)

categories = Category.objects.all()

tags = Tag.objects.all()

return render(request, 'category.html', {

'site': site,

'posts': posts,

'category': requested_category,

'categories': categories,

'tags': tags,

})

djangoBlog/urls.py

path('category/<slug:slug>', views.category, name='category'),

Here we passed an extra variable, slug, from the URL to the view function, and on lines 3 and 4, we used that variable to find the correct category and posts.

- The

tagview

blog/views.py

def tag(request, slug):

site = Site.objects.first()

posts = Post.objects.filter(tag__slug=slug).filter(is_published=True)

requested_tag = Tag.objects.get(slug=slug)

categories = Category.objects.all()

tags = Tag.objects.all()

return render(request, 'tag.html', {

'site': site,

'posts': posts,

'tag': requested_tag,

'categories': categories,

'tags': tags,

})

djangoBlog/urls.py

path('tag/<slug:slug>', views.tag, name='tag'),

- The

postview

blog/views.py

def post(request, slug):

site = Site.objects.first()

requested_post = Post.objects.get(slug=slug)

categories = Category.objects.all()

tags = Tag.objects.all()

return render(request, 'post.html', {

'site': site,

'post': requested_post,

'categories': categories,

'tags': tags,

})

djangoBlog/urls.py

path('post/<slug:slug>', views.post, name='post'),

Create the template layer

For the templates, instead of writing your own code, you may use the template we've created here.

This is the template structure we are going with.

templates

├── category.html

├── home.html

├── layout.html

├── post.html

├── search.html

├── tag.html

└── vendor

├── list.html

└── sidebar.html

The layout.html contains the header and the footer, and it is where you import the CSS and JavaScript files. The home, category, tag and post are the templates that the view functions point to, and they all extends to the layout. And finally, inside the vendor directory are the components that will appear multiple times in different templates, and you can import them with the include tag.

layout.html

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="IE=edge" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0" />

{% load static %}

<link rel="stylesheet" href="{% static 'style.css' %}" />

{% block title %}{% endblock %}

</head>

<body class="container mx-auto font-serif">

<nav class="flex flex-row justify-between h-16 items-center border-b-2">

<div class="px-5 text-2xl">

<a href="/"> My Blog </a>

</div>

<div class="hidden lg:flex content-between space-x-10 px-10 text-lg">

<a

href="https://github.com/thedevspacehq"

class="hover:underline hover:underline-offset-1"

>GitHub</a

>

<a href="#" class="hover:underline hover:underline-offset-1">Link</a>

<a href="#" class="hover:underline hover:underline-offset-1">Link</a>

</div>

</nav>

{% block content %}{% endblock %}

<footer class="bg-gray-700 text-white">

<div

class="flex justify-center items-center sm:justify-between flex-wrap lg:max-w-screen-2xl mx-auto px-4 sm:px-8 py-10">

<p class="font-serif text-center mb-3 sm:mb-0">

Copyright ©

<a href="https://www.ericsdevblog.com/" class="hover:underline"

>Eric Hu</a

>

</p>

<div class="flex justify-center space-x-4">. . .</div>

</div>

</footer>

</body>

</html>

There is one thing we need to talk about in this file. Notice from line 7 to 8, this is how you can import static files (CSS and JavaScript files) in Django. Of course, we are not covering CSS in this tutorial, but we have to talk about how it can be done if you do need to import extra CSS files.

By default, Django will search for static files in individual app folders. For the blog app, Django will go to /blog and search for a folder called static, and then inside that static folder, Django will look for the style.css file, as defined in the template.

blog

├── admin.py

├── apps.py

├── __init__.py

├── migrations

├── models.py

├── static

│ ├── input.css

│ └── style.css

├── tests.py

└── views.py

home.html

{% extends 'layout.html' %}

{% block title %}

<title>Page Title</title>

{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<div class="grid grid-cols-4 gap-4 py-10">

<div class="col-span-3 grid grid-cols-1">

<!-- Featured post -->

<div class="mb-4 ring-1 ring-slate-200 rounded-md hover:shadow-md">

<a href="{% url 'post' featured_post.slug %}"

><img

class="float-left mr-4 rounded-l-md object-cover h-full w-1/3"

src="{{ featured_post.featured_image.url }}"

alt="..."

/></a>

<div class="my-4 mr-4 grid gap-2">

<div class="text-sm text-gray-500">

{{ featured_post.created_at|date:"F j, o" }}

</div>

<h2 class="text-lg font-bold">{{ featured_post.title }}</h2>

<p class="text-base">

{{ featured_post.content|striptags|truncatewords:80 }}

</p>

<a

class="bg-blue-500 hover:bg-blue-700 rounded-md p-2 text-white uppercase text-sm font-semibold font-sans w-fit focus:ring"

href="{% url 'post' featured_post.slug %}"

>Read more →</a

>

</div>

</div>

{% include "vendor/list.html" %}

</div>

{% include "vendor/sidebar.html" %}

</div>

{% endblock %}

Notice that instead of hardcoding the sidebar and the list of posts, we separated them and placed them in the vendor directory, since we are going to use the same components in the category and the tag page.

vendor/list.html

<!-- List of posts -->

<div class="grid grid-cols-3 gap-4">

{% for post in posts %}

<!-- post -->

<div class="mb-4 ring-1 ring-slate-200 rounded-md h-fit hover:shadow-md">

<a href="{% url 'post' post.slug %}">

<img

class="rounded-t-md object-cover h-60 w-full"

src="{{ post.featured_image.url }}"

alt="..." />

</a>

<div class="m-4 grid gap-2">

<div class="text-sm text-gray-500">

{{ post.created_at|date:"F j, o" }}

</div>

<h2 class="text-lg font-bold">{{ post.title }}</h2>

<p class="text-base">{{ post.content|striptags|truncatewords:30 }}</p>

<a

class="bg-blue-500 hover:bg-blue-700 rounded-md p-2 text-white uppercase text-sm font-semibold font-sans w-fit focus:ring"

href="{% url 'post' post.slug %}"

>Read more →</a

>

</div>

</div>

{% endfor %}

</div>

From line 3 to 25, recall that we passed a variable posts from the view to the template. The posts contains a collection of posts, and here, inside the template, we iterate over every item in that collection using a for loop.

Line 6, remember that we created a URL dispatcher like this:

path('post/<slug:slug>', views.post, name='post'),

In our template, {% url 'post' post.slug %} will find the URL dispatcher with the name posts, and assign the value of post.slug to the variable <slug:slug>, which will then be passed to the corresponding view function.

Line 14, the date filter will format the date data that is passed to the template since the default value is not user-friendly. You can find other date formats here.

Line 17, here we chained two filters to post.content. The first one removes the HTML tags, and the second one takes the first 30 words and slices the rest.

vendor/sidebar.html

<div class="col-span-1">

<div class="border rounded-md mb-4">

<div class="bg-slate-200 p-4">Search</div>

<div class="p-4">

<form action="" method="get">

<input

type="text"

name="search"

id="search"

class="border rounded-md w-44 focus:ring p-2"

placeholder="Search something..." />

<button

type="submit"

class="bg-blue-500 hover:bg-blue-700 rounded-md p-2 text-white uppercase font-semibold font-sans w-fit focus:ring">

Search

</button>

</form>

</div>

</div>

<div class="border rounded-md mb-4">

<div class="bg-slate-200 p-4">Categories</div>

<div class="p-4">

<ul class="list-none list-inside">

{% for category in categories %}

<li>

<a

href="{% url 'category' category.slug %}"

class="text-blue-500 hover:underline"

>{{ category.name }}</a

>

</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

</div>

</div>

<div class="border rounded-md mb-4">

<div class="bg-slate-200 p-4">Tags</div>

<div class="p-4">

{% for tag in tags %}

<span class="mr-2">

<a href="{% url 'tag' tag.slug %}" class="text-blue-500 hover:underline"

>{{ tag.name }}</a

>

</span>

{% endfor %}

</div>

</div>

<div class="border rounded-md mb-4">

<div class="bg-slate-200 p-4">More Card</div>

<div class="p-4">

<p>. . .</p>

</div>

</div>

</div>

category.html

{% extends 'layout.html' %}

{% block title %}

<title>Page Title</title>

{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<div class="grid grid-cols-4 gap-4 py-10">

<div class="col-span-3 grid grid-cols-1">

{% include "vendor/list.html" %}

</div>

{% include "vendor/sidebar.html" %}

</div>

{% endblock %}

tag.html

{% extends 'layout.html' %}

{% block title %}

<title>Page Title</title>

{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<div class="grid grid-cols-4 gap-4 py-10">

<div class="col-span-3 grid grid-cols-1">

{% include "vendor/list.html" %}

</div>

{% include "vendor/sidebar.html" %}

</div>

{% endblock %}

post.html